I felt that on balance this course delivered very well on its expectations of educating students on the "People, Places, and Culture" of Latin America. I was extremely impressed with the depth of content on a wide range of topics, which went well below the superficial level to give students a true perspective on this dynamic region of the world. I also felt that the many varied assignments within the blog portfolio helped us as students to get our hands dirty, requiring us to deeply engage with the class material. This hands on approach went well beyond simple memorization of facts, allowing the content to come alive and become more engrained with students due to the critical analysis and research required.

My one critique would be the fact that all of the assignments were not chronologically separated throughout the course as far as due dates. Not so much that I felt a traditional structure was needed to help students complete assignments on time. We are all adults and can structure our time accordingly to ensure all assignments were complete by the last class deadline. It was an issue for me because we were not able to get back any marks for our assignments, which meant we had no concrete feedback on how we were doing in the course and if our work was meeting your expectations.

Overall I definitely enjoyed the course and would recommend it to other students.

Wednesday, 20 June 2012

Ethnography Review - Intimate Enemies

Introduction

Intimate Enemies: Landowners, Power, and Violence in Chiapas is an academic ethnography (272 pages), written by Aaron Bobrow-Strain and published in 2007 by Duke University Press. His work closely examines the conflict between landowning elites and the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberacion Nacional (EZLN), a rebellious rural movement that led a successful agricultural land reclamation campaign on behalf of the lower class indigenous people in the southeastern Mexican state of Chiapas (see figure 1.0 below). Bobrow-Strain’s ethnographic research was focused on the real-life accounts and perspectives of the elite landowners in this conflict. This report will provide a brief summary of Bobrow-Strain’s main points and thesis for examination within the ethnography, and an evaluation of how effectively they are born out and aesthetically delivered to the audience within the text.

Background Analysis

Beginning in 1994, The EZLN, along with the aid of other affiliated and unaffiliated rural movements, launched a series of reclamation invasions of agricultural land against ladino landowners. These elite landowners, many of which had owned their large fertile tracts of land for generations, suddenly were embroiled in a sociopolitical uprising that threatened their previously unchallenged land ownership. Bobrow-Strain states, these landowning elites were being painted as a violent and powerful class of modern “latifundistas”, a historical reference to privileged landowners of Spanish dissent which owned extensive estates of land, cultivated on the backs of Latin American indigenous slave labour.

Contrary to this wholly violent representation, many elite landowners met the resistance of these rebel invaders with resignation, rather than violence. Despite the outcry from landowners to the Mexican government, only a small percentage of these invaders were evicted. As public pressure mounted from outraged landowners, the government response was the adoption of the Agrarian Accords in 1996. This historic accord involved the government purchasing massive quantities of the agricultural land and redistributing it to the poor indigenous communities through state-subsidized programs. Ultimately, the indigenous people of the region were relatively victorious in this contentious, and sometimes violent, struggle, ending generations of land monopolization and forcing the migration of many of these elite landowners out of Chiapas, Mexico.

Thesis Analysis

Bobrow-Strain’s ethnography does not follow the romantic struggle of the down-trodden indigenous people of Chiapas as one might expect. Rather, it takes up the unique, and perhaps politically incorrect, position of empathizing with the elite landowners in an attempt to tell the story of this struggle for territory and rights from their perspective. This approach was taken by the author in order to critically explore the overly simplified notion that this conflict was a strict dichotomy of the repressed good (peasants) versus an evil oppressor (landowners). Bobrow-Strain was not without his own reservations in spotlighting the views of the elite at the expense of the indigenous perspective. He addressed this internal conflict as he writes, “I feared that my work might unintentionally undermine efforts to transform relations of domination and repression in the Chiapan countryside”. His unique perspective does much to further our holistic understanding of the conflict in Chiapas, simply through his willingness to offer a platform to the privileged, and perhaps previously unsympathetic, voice of the elite landowners. Todd Hartch concurred in a 2008 review for the American Historical Review in which he wrote, “This is an important book that explains how landowners responded to the various pressures and tensions of their position as local elites”.

While many may see the struggle for land reclamation by previously subjugated indigenous communities as a wholly righteous enterprise, there are many moral and practical considerations which complicate the issue with ambiguous shades of grey, which are explored within Bobrow-Strain’s ethnographic research. In an Oxfam review in 2008, Debroah Eade summed up the challenge Bobrow-Strain’s ethnographic thesis presents when she observed, “Borrow-Strain sets himself the difficult task of challenging the dualism of ‘good’ indigenous peasants with ‘bad’ ladino landowners”. Bobrow-Strain conducted extensive research by interviewing fifty landowners from four generations of the elite class. His findings through his ethnographic research brought much to light that would challenge this dualism of good and bad, even amongst many proponents of the indigenous perspective.

Perhaps the strongest of these practical considerations is the lack of experience maintaining and developing agricultural lands amongst indigenous populations of Mexico, contrasted against the inherent generational knowledge and experience of now transplanted former elite landowners. Experts in land cultivation for commercial profit, lands that were once rich in agriculture under the old regime of elite landowners, are often now planted only with corn or neglected altogether. Don Roberto, one of the former elite landowners Bobrow-Strain interviewed, reflected on the transformation of his land and that of his friends, post-indigenous land reclamation. Bobrow-Strain writes, “… the conversion of pasture to vast stretches of ‘unproductive’ wild land … symbolize the waste and devastation wrought by the transfer of land to indigenous communities after the 1994 invasions”.

Form a purely moral perspective; while many of these elite landowners had the still fresh blood of subjugation, violence and racism on their hands from their past dealings with the indigenous factions that were now rising up against them, they are still human beings with basic rights. Forcibly invading the land of these ladinos, many of which have owned these plots in their families for generations, by way of a type of Machiavellian means of violence is inherently wrong. While there may be ample justification in the motives of the EZLN, and other like minded rural activists, to regain their land and thereby dignity, achieving these aims by way of such brutal tactics in turn stains their hands with the same blood. Bobrow-Strain eloquently sums up this moral balance between the two sides when he writes, “… to replace landowners’ unmediated tale of innocence lost with a reiterated discourse of sweeping condemnation would substitute caricature for caricature …. I seek to replace the sharp dualisms of evil and good, landowner and peasant, with honest shadows."

Analysis and Evaluation

Unquestionably Bobrow-Strain’s ethnography succeeded in the main point of his thesis, showing that neither the landowners nor the peasants had the right to claim wholly righteous providence in this conflict. While he did not paint the elite landowners as sympathetic figures to be shown undue pity for their plight, Bobrow-Strain aptly demonstrated that the caricature of the evil landowner was just that. This critical view of the landowners as innocent victims of the conflict is illustrated in the passage, “I could never accept landowners’ decline as wholly unfortunate …” Through the ethnographic style of his research and documentation of his experiences with the real people embroiled in this historical conflict, Bobrow-Strain was able to lend personification to his writing detailing the landowners issues and perspective. Ultimately, he succeeded in walking the fine-line between empathy and sympathy, while remaining impartial and academically detached from the subjects of his research.

This academic detachment Aaron Bobrow-Strain was able to maintain, both during and in the eventual written accounts of his ethnographic research, is a product of his outsider’s perspective. While the author was eminently qualified to provide analysis of his subject material, having a PHD in Latin American Studies attained at the University of California, Berkeley and currently working as a professor of Political Studies at Whitman College (Aaron Bobrow-Strain, Whitman College), not being a native of Mexico with any ties or affiliations to either party in the conflict enabled this academic detachment.

From a personal perspective, I felt conflicted with my own internal cerebral and emotional reactions to this real-life conflict of the historically oppressed indigenous people of Chiapas as I read the book. Serving further proof that the author’s intent, to stimulate discourse and critical review of the events from both sides, was served. While one cannot help feeling sympathy and thereby justification for the actions of the rural activists to reclaim their ancestral lands, the accounts of the impacts and consequences of their actions on these very human landowners with families was cause for personal pause and reflection. One such passage that reflects the human reality behind the actions perpetrated against these vilified landowners reads, “The man had opened up his rich memory … his wife recounted in painful detail the violent events surrounding the invasion of their property.”

To say this ethnography was merely a socially and historically enlightening academic experience is to do the book a disservice. It was a riveting read that both engages and entertains while it educates on these important matters. The author’s first person dialogue as he navigates you through his experiences in dealing with both peasants and landowners, transports the reader to their time and place, while allowing you to feel their very real and human struggles and emotions. The author wrote the book with plain and simple language, without hiding behind academic prose, to allow the audience to feel the raw and very real lived experiences that were described within.

Conclusion

The desire to internalize simple binaries when viewing conflicts, such as good versus evil, is inherently human. As is the case with the land reclamation by the repressed poor of Chiapas pitted against the historically oppressive elite landowners of the region. However, as is invariably the case, these simple black and white binaries rarely provide a wholly accurate depiction of the events and contextual issues behind such conflicts. Aaron Bobrow-Strain’s important ethnographic research, which details the conflict from the perspective of the elite or ‘evil’ landowners, does much to restore a balanced perspective to this polarizing conflict. While certainly his documented research and analysis was not biased towards the landowners, it provided them with a voice to better understand the conflict in a more holistic way than had been predominantly presented within the public sphere previously.

References

Eade, Deborah (2008). A Review of Intimate Enemies: Landowners, Power, and Violence in Chiapas and Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask. Oxfam GB, 18(3), 453-456.

Hartch, Todd (2008). A Review of Intimate Enemies: Landowners, Power, and Violence in Chiapas. The American Historical Review, 113(3), 882-883.

“Aaron Bobrow-Strain”, Whitman College, accessed June 20, 2012, http://www.whitman.edu/content/politics/faculty/aaron-bobrow-strain

Fictional Book Review - Death in the Andes

Introduction

Death In The Andes is a novel that was written in 1993 by Mario Vargas Llosa. It was translated from its original Spanish text into English (276 pages) in 1996 by Edith Grossman, and published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, Inc. While it is difficult to pigeon-hole this novel into a specific genre, murder mystery would be a functional one strictly for the purposes of classification. The primary aim of this book review will be to provide a brief synopsis on the plot, and perhaps more importantly to explore and analyze the general themes and purposes behind the author’s intended messages. Further, to provide reflections on what was derived from the novel from both a literary and a more visceral personal perspective.

Plot Summary

Death in The Andes is a story which takes place in Naccos, a remote mining town situated in the Andean mountains of Peru, tucked away from the demands of modern urban life. A place inhabited by the Serruchos, indigenous rural mountain people of Peru that speak the indigenous Quechua language. The story is mainly told from the perspective of the main protagonist Lituma, a Corporal in the Civil Guard of Spanish dissent. He is posted there to protect a highway construction crew of 200 workers against the Senderistas, guerrilla terrorists of the Shining Path.

Lituma sums up the central fulcrum from which the axis of the story revolves when he states, “… what’s going on? First the mute, then the albino, now one of the highway foremen.” A series of mysterious disappearances in Naccos that Lituma is determined to resolve a reason for. These mysterious disappearances ominously foreshadow a series of further killings in the region, which in isolation have no inherent meaning, but collectively forge the major thematic devices of the narrative.

The primary suspects of the original disappearances are the ruthless and dispassionate Senderista guerillas; who have taken on the grizzly mission to kill any foreigners that should enter the Andes, without cause or reason other than their alien status. Later, the more disturbing realization manifests that the disappearances are at the hands of the Serrucho mountain people, having reverted to the cannibalistic rituals of the early indigenous cultures of the region. Their tradition dictates they offer up humans for sacrifice before the undertaking of any major construction project, in this case the highway being built in Naccos.

While these are the main features of the plot, as it relates to its overarching theme of cultural conflict, there are a series of minor subplots woven throughout the book that are seemingly divorced from the primary thematic structure. One such subplot is a love story between Carreño, a Civil Guardsman working under Lituma, and a prostitute he encounters. These plot tangents made for an oft fractured and at times disjointed and confusing read. In a past 1996 review of the novel by Madison Bell she concurred remarking, “The foreground of this novel seems confusingly disorganized from start to finish. The individual vignettes are often brilliant, but neither Lituma nor the reader nor perhaps the author himself can put them all coherently together”.

Theme Analysis

While many sub-themes could be interpreted and explored, including a number of allusions to Greek mythology and tragedy which are present within the text, the overarching theme, which is ubiquitous throughout, is that of conflict and intolerance between indigenous cultures and the capitalist ideologies of the Western world. A clash of worlds and the cultural confusion that results are aptly summarized when Lituma states, when commenting on the mountain people, “Because you're mysterious and I don't understand you … I like people to be transparent.” This observation is consistent with the historical context of the Spanish Conquistadores view on the natives they first encountered during the conquests. Such was the vast extent of disconnect between the two groups, Spanish colonizers ethnocentric perspective questioned if the natives were more animal than human. Historically, this disassociation with the native’s humanity provided justification for the European settlers to barbarically slaughter the “others” to achieve their own gains. Specifically within the real historical contextual background of Peru, their once proud Inca Empire was completely extinguished in 1532 by a group of Spanish conquistadors, led by Francisco Pizarro, culminating in the defeat and capture of Inca Emperor Atahualpa (Spain, 1841).

In a true reversal of fortune from the historical script, in Death in the Andes it is the indigenous people that are vengefully treating the Europeans as less than human. Killing the “others”, as if they were animals fit for slaughter, in numbers at their own digression and to meet their own ends. Seemingly executed simply for the crime of being an outsider to the region, in one chapter a pair of French tourists are introduced, only to be killed off quickly after by way of stoning. This disassociation with the violence the indigenous people are a party to is encapsulated when the main protagonist Lituma states, “All those deaths just slide right off the mountain people”.

There is much stark symbolism than can be interpreted based on the description of the three key figures, whose disappearance and subsequent ritualistic murders at the hands of the indigenous mountain people are the central basis for the plot. The “albino” can clearly be interpreted as the symbolic incarnation of the European or “white man”. The mute, himself a Siucani native of indigenous dissent, is a more subjective and complex interpretation. Perhaps through the killing of the mute, or man without a voice, the indigenous people are symbolically ending their silence and lack of social and political power as a result of the subjugation from the Europeans. The highway construction foremen or “boss” could be viewed as the symbol of insidious European power over native culture.

I believe the purpose of these thematic devices was not intended by the author to be taken in literal terms. We as the audience should not infer from the narrative that the author is in support of bloody and violent retribution, in the form of a revolt and mass killings of Europeans at the hands of indigenous people. Rather, the intent was to illustrate the absurdity of the inhumane treatment the natives endured through the subjugation of its people historically, simply for being different physically and culturally. The author deftly is able to build empathy from the reader for the past, and current, treatment of indigenous cultures by showing the atrocities of ethnocentricity from a reverse perspective. Therefore, the overriding message is that we must strive for a balance of equality and power, returning the voice and dignity to indigenous cultures. Moreover, we should seek to mitigate cultural confusion by attempting to understand and respect cultural differences between diverse groups.

Llosa’s message involving the historical context of the Spanish conquest, and atrocities that followed as a result of cultural confusion and intolerance, is one that is deeply engrained as part of the Latin American experience. We see it in all forms of Latin American artistic expression, including in the subject matter of many of the globally recognized works of muralist Diego Rivera. Additionally, being such a highly socially aware and political message at its heart, it should be no surprise that the author himself is deeply politically engaged. In fact, In 1990 Mario Vargas Llosa ran for the Presidency of his homeland Peru. He garnered a plurality of 29 percent in the first round of balloting but lost the runoff to an obscure agronomist named Alberto Fujimori, who received 57 percent of the final vote (Kellman, 1996).

Overall Analysis and Evaluation

On balance, I would recommend this book as an interesting read, able to deliver a powerful message though its socially and politically aware themes. It was apparent that the author, of Peruvian dissent himself, was speaking from a place of knowledge and experience which revealed itself through the authenticity and honesty of his writing. Llosa’s knowledge and mastery of his subject matter was illustrated through his intimate understanding of indigenous Peruvian cultural practices and political movements, explored in detail throughout the narrative. For example, the Shining Path is a contemporary Maoist political movement that exists in Peru, and wields its power through violent guerrilla tactics of terrorism (Shining Path, Britannica), as portrayed in the book. Additionally, his real-life involvement with Peruvian politics infuses ethos to the politically loaded messages throughout the construct of the narrative.

This authenticity was enhanced by the casual style of the writing and dialogue, which was gritty and reflective of the everyday people, embroiled in this plot of extraordinary circumstances. One such example was a line in which Lituma states, “Fix us some coffee for this shit weather.”, clearly Llosa’s dialogue was not confined by any pretense or attempts to create poetic prose, rather used as a means by which to reflect the authenticity of everyday life.

While the dialogue and character development was without artistic ambiguity as a result of pretense, the numerous allusions to past cultural texts, and some seemingly disjointed and unimportant sub-plots, made the reading a laborious task at times to form congruency and clarity of plot and message.

Putting aside these shortcomings, from a holistic perspective, the book had an important message that was delivered with a “readable” aesthetic of down to earth real-life appeal. Like any great novel should, it engaged the reader with interesting dialogue and character development, while also providing the reader with important messages of meaning for reflection. The author ultimately succeeded in conveying his message of the importance of cultural understanding and equality, amongst the diverse and often fractured people of Latin America.

Conclusion

In conclusion, despite the complexities and many layers of the author’s writing style, in Death in the Andes; Llosa has been able to subversively, yet unmistakably, portray an important social and political message of the negative consequences of cultural intolerance. Through a clever juxtaposition of the historical power balance between indigenous and European culture, the audience cannot help but gain a perspective of empathy for the historical injustices and violence perpetrated against the indigenous cultures of Latin America. The credibility and experiential knowledge the author brings to his subject matter, further serves to validate and underscore this work as an important and distinctive piece of Latin American literature.

References

Bell, Madison (1996), Mountains of the Mind, New York Times, accessed June 12, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/06/28/specials/llosa-andes

Kellman, Steven G. (1996), Vargas Llosa Returns to His Peaks, The Atlantic Monthly Online, accessed June 18, http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/96mar/vargasl

“Shining Path”, Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed June 19, 2012,

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/540794/Shining-Path

Spain (1841), Recopilación de leyes de los Reynos de las Indias, Boix, Oxford University Archives.

Monday, 18 June 2012

Latin American Social Movements

The array of images below represent some of the major historical nationalist, labour and rural movements throughout Latin America.

Peronismo: Images below depict the leader of the nationalist movement General Juan Perón of Argentina, and a poster from Brazil promoting the movement that spead throughout Latin America.

ntina

Cardenismo: Images below depict the leader of the nationalist movement General Lázaro Cárdenas, and a book cover of "El Cardenismo", a book on the movement by Mexican author Roberto Blanco Moheno

Castrismo: Images below depict its charasmatic Cuban leader Fidel Castro, and a poster from his native Cuba promoting the movement.

Chavismo: Images below depict Hugo Chavez, the Venezuelan leader of the nationalist movement, along with an emblem for the cause.

Sandinismo: Images below depict Nicaraguan General Sandino for whom this nationalist movement was named, and a propogandic painting of the movement.

Paros Cívicos: A Latin American labour movement started in Colombia. Images below depict an official poster adverstising the movement, a protestors banner at a demonstartion in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and demonstartors in Honduras.

Contag: Images below depict the emblem of the movement, started in the 1980's, for the rural poor in Brasil, along with an image of its supporters.

Brazilian MST (Landless Movement): Images below depict the emblem of the rural movement for the redistribution of land, along with a massive demonstartion of its supporters in Brasil.

Shining Path: Images below depict a poster promoting the Maoist communist values of this rural movement from Peru, and an image of some of its violent geurilla members.

Zapatistas: Images below depict two women holding up the emblem of this Mexican rural movement (ELZN - Ejercito Zapatista de Liberacion Nacional ), and an image of some of its geurilla fighters.

Sunday, 10 June 2012

Mundo Quino Comic Strip

Below is a Quino comic strip I found particularly interesting. It illustrates Quino's cerebral social commentary using only symbolism and imagery to guide the reader. As Quino mentioned in his interview with Lucía Iglesias Kuntz, he prefers to let images speak in his work as a stand-alone product whenever possible.

In the strip he makes an allusion to Rodin's famed sculpture the thinker, this image is juxtaposed against modern technology from our new industrial society, in the form of a "super computer". Further, the strip details the old world human "thinker" being abandoned and carried away, while the piece of modern technology is being worked on by one man and admired by two others, effectively replacing the sculpture with modern technology.

I think the social commentary Quino is making in this comic strip is that old world values of human thought and creativity are being replaced by man's zeal for technology and industrial automation in the capitalist economy. In essence, man is losing the ability to think creatively and critically due to a reliance on modern technology to do the thinking for us.

In the strip he makes an allusion to Rodin's famed sculpture the thinker, this image is juxtaposed against modern technology from our new industrial society, in the form of a "super computer". Further, the strip details the old world human "thinker" being abandoned and carried away, while the piece of modern technology is being worked on by one man and admired by two others, effectively replacing the sculpture with modern technology.

I think the social commentary Quino is making in this comic strip is that old world values of human thought and creativity are being replaced by man's zeal for technology and industrial automation in the capitalist economy. In essence, man is losing the ability to think creatively and critically due to a reliance on modern technology to do the thinking for us.

Friday, 1 June 2012

Muralists and Painters of Latin America

Latin America can be proud of the rich heritage of muralists and artists throughout its history. I am especially stuck by the technical brilliance of Diego Rivera and the bold and brutally honest self reflection of Frida Kahlo.

Diego Rivera: His work is not only aesthetically striking, but it also incorporates historical context and social issues relevant for his day. From a technical perspective the pain-staking detail and grandness of his murals are an astonishing artistic achievement to behold. His frescos remind me of the great Italian renaissance painter Michelangelo in both their technical proficiency and subject matter. Below are two of my favourite examples of his work that display his technical brilliance and social/historical commentary.

Exploitation of Mexico by Spanish Conquistadors - This painting showcases Rivera's technical ability and attention to detail, while displaying his social conscience in his subject matter. A commentary on the brutal subjugation of the indigenous Mexican people by the Spanish.

Exploitation of Mexico by Spanish Conquistadors, Mexico City - Palacio Nacional.

Mural (1929-1945) by Diego Rivera

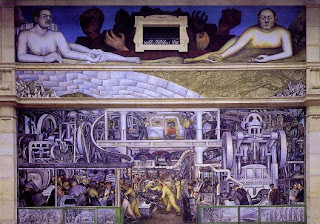

Detroit Industry - Again note the exquisite attention to detail and impressive laer-than-life scope of his work. A social commentary on the capitalist establishment in the United States by the openly communist artist.

Detroit Industry, Detroit Institute of Arts. Mural (1932-1933) by Diego Rivera

Frida Kahlo: What she may have lacked in technical proficiency relative to the great masters, she more than made up for with her bold, honest and provocative style. Her self-portraits are deeply honest and boldly evoke the pain of the human condition without compromise. Her prolific work as an artist is all the more remarkable given the struggles with her health throughout her life and her complete lack of formal training. Below are two of my favourite examples that illustrate the boldness and pathos her work displays.

The Broken Column - A brutally expressive self portrait examining her personal emotional and physical pain.The broken column representing the physical pain throughout her life as a result of her shattered spine from a bus accident at an early age. The nails representative of her emotional pain. The largest one to her heart depicting her tumultuous relationship with Diego Rivera.

The Broken Column, Self-Portrait by Frida Kahlo 1944

The Two Fridas - Another stark and honest reflective self portrait. The two Fridas representing her two selves, the European and Latin Frida. Both Fridas shown us having been stripped of their heart and identity.

The Two Fridas, Self-Portrait by Frida Kahlo 1939

Map of Latin American Music Styles

While certainly many of the Latin musical genres are widely enjoyed accross Latin America, the map below charts the major origins of the rich diversity that makes up the mosaic of Latin American musical styles.

As the map illustates much of the delvelopment of Latin musical culture can bet attributed to the nations of Mexico, Cuba and Brazil.

As the map illustates much of the delvelopment of Latin musical culture can bet attributed to the nations of Mexico, Cuba and Brazil.

A Passion for the Beautiful Game

Football (or Soccer) is a great passion of Latin American culture. It could be argued that no other region of the world embraces the game with as much passion and reverance as the Latino people. This passion is evidenced by the great success its nations have enjoyed on the grandest global stage of the World Cup.

The World Cup has been contested 19 times since its creation in 1930, and Latin American nations have captured the trophy an amazing 9 times, including a record 5 times by Brazil!

List of Latin American World Cup Winners

2002 Brazil

1994 Brazil

1986 Argentina

1978 Argentina

1970 Brazil

1962 Brazil

1958 Brazil

1950 Uruguay

1930 Uruguay

Latin America also boasts the origins of arguably the two greatest players in the history of the game, Pelé and Diego Maradona. Pelé led his native Brazil to World Cup glory in 1958, 1962 and 1970, while Maradona led his Argentine side to the trophy in 1986.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento (Pele) - born in Brazil October 21, 1940

Known by his nickname Pelé, widely regarded as the best football player of all time. In 1999, he was voted Football Player of the Century by the IFFHS. In 1999 the International Olympic Committee named Pelé the "Athlete of the Century". In his native Brazil, Pelé is hailed as a national hero. He is known for his accomplishments and contributions to the game of football (Wikipedia).

Diego Armando Maradona Franco - born in Argentina October 30, 1960

Many people, experts, football critics, former and current players consider Maradona the greatest football player of all time. He won FIFA Player of the Century award which was to be decided by votes on their official website, their official magazine and a grand jury (Wikipedia).

The World Cup has been contested 19 times since its creation in 1930, and Latin American nations have captured the trophy an amazing 9 times, including a record 5 times by Brazil!

List of Latin American World Cup Winners

2002 Brazil

1994 Brazil

1986 Argentina

1978 Argentina

1970 Brazil

1962 Brazil

1958 Brazil

1950 Uruguay

1930 Uruguay

Latin America also boasts the origins of arguably the two greatest players in the history of the game, Pelé and Diego Maradona. Pelé led his native Brazil to World Cup glory in 1958, 1962 and 1970, while Maradona led his Argentine side to the trophy in 1986.

Known by his nickname Pelé, widely regarded as the best football player of all time. In 1999, he was voted Football Player of the Century by the IFFHS. In 1999 the International Olympic Committee named Pelé the "Athlete of the Century". In his native Brazil, Pelé is hailed as a national hero. He is known for his accomplishments and contributions to the game of football (Wikipedia).

Diego Armando Maradona Franco - born in Argentina October 30, 1960

Many people, experts, football critics, former and current players consider Maradona the greatest football player of all time. He won FIFA Player of the Century award which was to be decided by votes on their official website, their official magazine and a grand jury (Wikipedia).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)